Tropical cyclones in the Northwest Pacific are a major driver of flood risk across Southeast and East Asia. In 2025, storm numbers were close to long term averages, but westward shifting tracks and late season extremes brought severe rainfall and flooding. JBA Climate Scientists Jack Giddings and Andrew Magee explore what shaped the season and what it means for flood risk and resilience.

Ready to discuss your next project? Contact our team today.

Tropical cyclones are a major driver of flood risk across Southeast and East Asia, shaping humanitarian impacts, economic losses, and long-term development outcomes. In the Northwest Pacific, the world’s most active tropical cyclone basin, subtle shifts in storm behaviour can translate into major differences in impact, location, and severity.

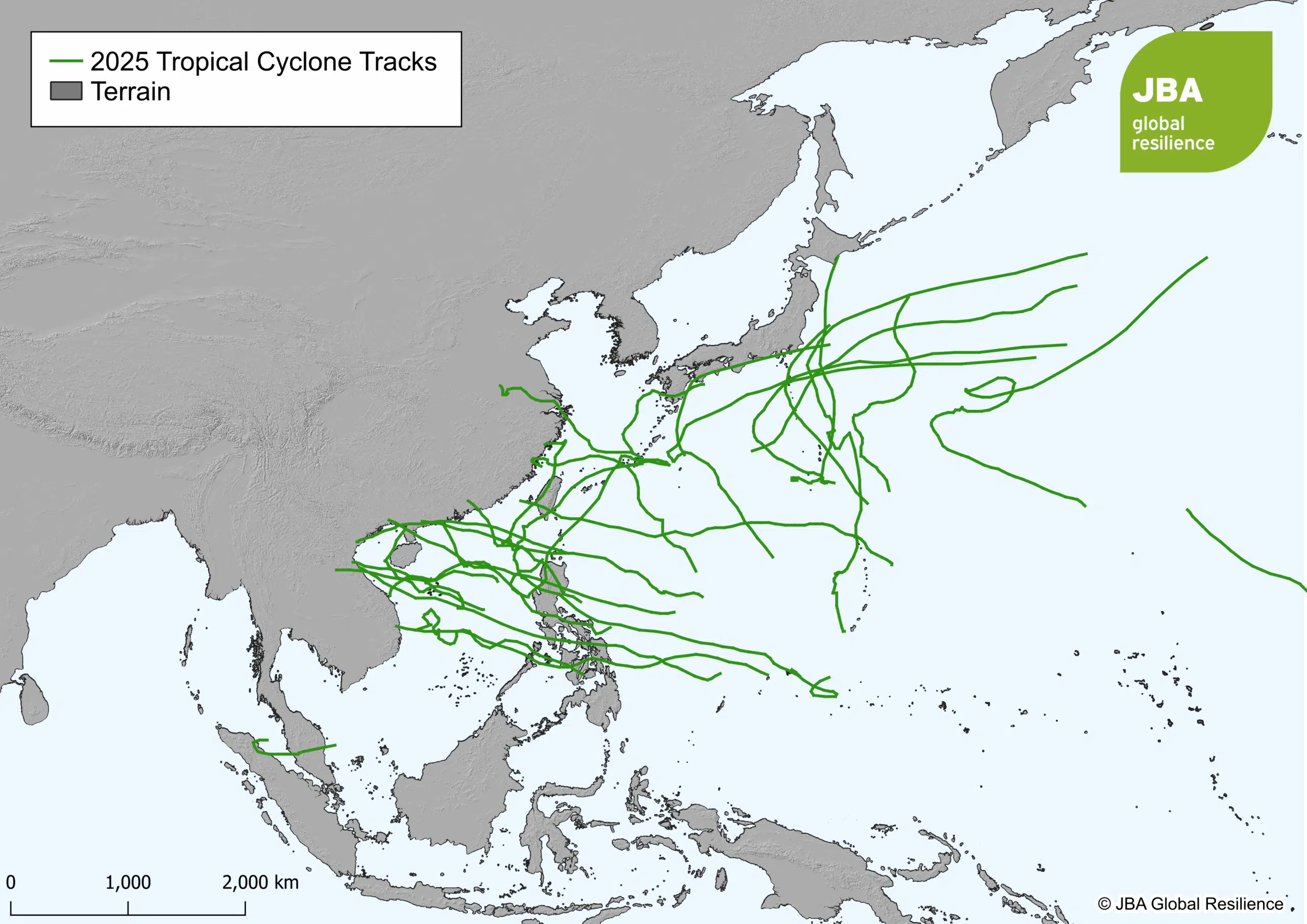

The 2025 Northwest Pacific tropical cyclone season illustrates this sensitivity clearly. While overall storm numbers were broadly in line with the long-term average, their formation, movement and impact were far from typical. A greater proportion of storms tracked westwards across Southeast Asia, leading to repeated landfalls in countries such as the Philippines and Vietnam. This contributed to widespread flooding and severe impacts, while northeast Asia was largely spared the most damaging weather systems.

Preliminary estimates suggest that Northwest Pacific typhoons caused approximately US$11 billion in damages in 2025, accounting for around half of total tropical cyclone losses across all Northern Hemisphere basins (Munich Re, 2025). These impacts reflect not only the characteristics of individual storms, but also the influence of large-scale climate dynamics shaping where, when and how cyclones formed and tracked during the season.

During 2025, 28 named tropical cyclones formed in the Northwest Pacific, with 13 reaching typhoon strength, where maximum sustained wind speeds exceed 118km/h. Five of these intensified into super typhoons, a severe tropical cyclone where wind speeds exceed 185 km/h (Hong Kong Observatory, 2025). This level of activity is slightly above, but broadly consistent with, the long-term average of 26 named tropical cyclones per year observed between 1981 and 2010 (Zhan et al., 2012).

The season began relatively quietly. The first named typhoon, Wutip, formed in mid-June and impacted the Philippines. Activity then remained below average through much of the early peak season, with fewer storms than usual through July and August (NASA, 2025a). This early period of below-average activity was followed by a marked increase in late September, when Super Typhoon Ragasa underwent rapid intensification and reached maximum sustained winds of approximately 270 km/h. Ragasa made landfall in northern Luzon (Philippines) before affecting parts of China and Vietnam.

Late season activity was dominated by several high-impact tropical cyclones, including Neoguri, Bualoi, Matamo, Kalmaegi, Fung-Wong and Koto (Figure 1). The costliest event was Typhoon Matamo, which drove widespread coastal and inland flooding across the Philippines, Taiwan, China, Vietnam and Thailand causing an estimated US$3.5 billion in losses (Munich Re, 2025).

Tropical cyclone behaviour in the Northwest Pacific (and in other basins) is strongly influenced by large-scale climate variability, particularly the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD). These drivers shape sea surface temperatures and atmospheric circulation, influencing where convection is most likely to organise into tropical cyclones.

During early 2025, ENSO conditions were characterised by a La Niña phase, with cooler-than-average sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific and warmer-than-average conditions in the western Pacific (NCEP, 2025). After a brief neutral period, La Niña conditions returned later in the year.

These conditions favoured enhanced convection over the western Pacific, contributing to a westward shift in cyclone formation and tracks. As a result, a higher proportion of storms moved towards Southeast Asia, increasing landfall frequency across the Philippines, Vietnam and southern China (Figure 2).

Sea surface temperature variability in the Indian Ocean, associated with the IOD, likely also contributed. Conditions were broadly neutral through mid-2025, before shifting towards a negative IOD later in the year. Negative IOD conditions can strengthen and extend the monsoon trough westwards, supporting tropical cyclone development closer to the South China Sea and increasing the likelihood of landfall across Southeast Asia.

Together, these large-scale drivers help explain why impacts in 2025 were concentrated further west than in many recent seasons.

Figure 2: 2025 tropical cyclone tracks (solid dark green lines) sourced from IBTrACS across the Northwest Pacific basin.

While this article focuses on the Northwest Pacific, late 2025 also saw highly impactful tropical cyclones forming close to the Equator in adjacent basins. These events are relevant because they were influenced by the same circulation patterns shaping Northwest Pacific cyclone behaviour and produced severe rainfall-driven impacts across Southeast Asia.

One of the most notable events was Tropical Cyclone Senyar, which affected Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia. Senyar developed unusually late in the year and close to the Equator, where cyclone formation is typically limited by the weak Coriolis effect. Its development was supported by an exceptionally active Intertropical Convergence Zone, enhanced equatorial wave activity and warm sea surface temperatures, allowing the system to organise despite otherwise unfavourable conditions (Kew et al., 2025).

Although Senyar was not exceptional in terms of wind strength, its impacts were severe due to its slow movement. Weak background steering winds near the Equator caused the system to stall and loop over the Malacca Strait, resulting in prolonged and intense rainfall. Satellite-derived estimates from NASA’s Global Precipitation Measurement indicate that parts of Sumatra received up to 400 mm of rainfall during the event (NASA, 2025b).

A second late-season system, Tropical Cyclone Ditwah, developed in the North Indian Ocean and affected Sri Lanka. While outside the Northwest Pacific basin, Ditwah provides a useful regional example of rainfall‑driven cyclone risk. Like Senyar, Ditwah moved slowly due to weak steering winds, producing extreme rainfall that exceeded 350 mm in 24 hours in parts of Sri Lanka (ReliefWeb, 2025a).

Impacts from both systems were amplified by an already active monsoon season, with rainfall falling onto saturated catchments and steep terrain, triggering widespread flooding and landslides. Senyar affected an estimated 7.2 million people across Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia, while Ditwah affected around 1.6 million people in Sri Lanka, displacing more than 200,000 (ReliefWeb, 2025b).

Together, these events highlight two important considerations for disaster risk management in Southeast Asia:

Tropical cyclones already pose a significant flood risk across Southeast Asia, and climate change is expected to intensify several of their most damaging impacts. As global temperatures rise, the atmosphere’s capacity to hold moisture increases, creating conditions that can support heavier rainfall during storms (IPCC, 2023).

While future changes in Northwest Pacific tropical cyclone frequency remain uncertain, studies suggest that tropical cyclone rainfall rates may increase in a warming climate (Knutson et al., 2020). For climate-vulnerable countries across Southeast Asia, this translates into growing flood risk, with serious implications for livelihoods, food security and economic stability.

Evidence from recent events supports this signal. Attribution analyses of Tropical Cyclone Senyar suggest the storm was more intense in today’s warmer climate than it would have been in a cooler one. Sea surface temperatures were around 0.2°C higher than the 1999–2020 average (Alberti et al., 2025). A separate study estimated a 10% increase in both rainfall and wind strength (Kew et al., 2025).

Similar patterns were identified over central Vietnam in November 2025, where heavy rainfall associated with tropical cyclones was estimated to be around 15% higher than in a past climate (1950–1989). Modest increases in wind speed further enhanced moisture transport into coastal and mountainous regions, compounding flood risk (Faranda et al., 2025).

These climate-driven changes are interacting with development trends to amplify impacts. Rapid urbanisation across Southeast Asia has expanded exposure in flood-prone areas, while cascading failures across transport, energy and communications systems complicated response and recovery during the 2025 season. These disruptions disproportionately affected low-income and marginalised communities, who often have the least capacity to absorb and recover from shocks.

Addressing this growing risk requires an integrated approach to resilience. This includes improved hazard and impact modelling, impact-based early warning systems, anticipatory action, risk-informed planning and disaster risk financing. Strengthening institutional capacity and supporting locally grounded decision-making are equally important for reducing vulnerability and supporting more resilient development pathways.

The 2025 Northwest Pacific tropical cyclone season demonstrates how shifts in large-scale climate drivers and storm behaviour can result in disproportionate social and financial impacts. Westward-shifting cyclone tracks, slow-moving storms and near-equatorial systems combined to amplify flood risk across Southeast Asia.

As climate change continues to influence rainfall intensity and storm impacts, sustained investment in forecasting, early warning systems and integrated resilience planning will be essential to reduce future losses and support communities most exposed to flood risk.

Knutson, T.R. et al., 2020. Tropical Cyclones and Climate Change Assessment: Part II: Projected Response to Anthropogenic Warming. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 101(3), pp. E303–E322. [Accessed 8 January 2026].

Alberti, T., Faranda, D., Lucarini, V., & Mengaldo, G., 2025. Heavy rain in November 2025 Indonesian floods intensified by human-driven climate change. ClimaMeter, Institut Pierre Simon Laplace, CNRS. [Accessed 5 January 2025].

Faranda, D., Lucarini, V., Tang, H., & Mengaldo, G., 2025. Heavy rain in November 2025 Vietnam floods likely intensified by human-driven climate change. ClimaMeter, Institut Pierre Simon Laplace, CNRS. [Accessed 5 January 2025].

Hong Kong Observatory, 2025. Tropical Cyclone Classification. [Accessed 30 December 2025].

IPCC, 2023. Summary for Policymakers. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 1-34, doi: 10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.001. [Accessed 29 December 2025].

Munich Re, 2025. The 2025 hurricane and typhoon seasons: Gigantic storms, below-average losses. [Accessed 30 December 2025].

NASA, 2025a. Ragasa Steers Toward China. [Accessed 30 December 2025].

NASA, 2025b. Senyar Swamps Sumatra. [Accessed 30 December 2025].

NCEP, 2025. ENSO: Recent Evolution, Current Status and Predictions. [Accessed 30 December 2025].

Reliefweb, 2025a. Cyclone Ditwah Joint Rapid Needs Assessment: Phase 1 – Preliminary Scoping, 2 December 2025. [Accessed 6 January 2025].

Reliefweb, 2025b. Asia and the Pacific: Southeast and South Asia Cyclones and Floods Humanitarian Snapshot (Covering 17 November to 3 December 2025). [Accessed 30 December 2025].

Kew, S. et al., 2025. Increasing heavy rainfall and extreme flood heights in a warming climate threaten densely populated regions across Sri Lanka and the Malacca Strait (WWA scientific report No. 78). World Weather Attribution. [Accessed 5 January 2025].

Zhan, R., Wang, Y. & Ying, M, 2012. Seasonal forecasts of tropical cyclone activity over the Western North Pacific: A review. Trop. Cyclone Res. Rev. 1, 307–324. [Accessed 30 December 2025].

Ready to discuss your next project? Contact our team today.

Discover more about the challenges and solutions shaping resilience and sustainable development across the globe.