In FCV settings, early warning and forecasting systems can play a critical role in saving lives and livelihoods. But to be effective they must be trusted, usable and grounded in local realities. Hannah Measures, JBA specialist in Emergency Preparedness and Response, explores how early action is possible, even where systems are fragile.

Ready to discuss your next project? Contact our team today.

In fragile, conflict-affected and violent (FCV) settings, disasters compound existing vulnerabilities. When institutions are under strain and infrastructure is limited or subject to intentional damage, communities are often already facing acute risks. In these contexts, the impacts of climate-related hazards such as floods, storms or droughts can be devastating.

These settings are not defined solely by conflict. FCV contexts may involve political instability, economic fragility, protracted displacement or extended periods of post-disaster recovery – often in combination and often intensified by recurring shocks. Countries across Sub-Saharan Africa, South and Southeast Asia, the Middle East and Central America regularly face these intersecting vulnerabilities and hazard exposures.

Early warning and forecasting systems play a critical role in saving lives and livelihoods. But conventional approaches often fall short. To be effective, early warning in FCV settings must be adaptive, locally relevant, politically sensitive, and capable of fostering collaboration and trust.

Forecasting hazards provides decision-makers and communities with time. Time to act, time to protect, and time to prepare. In FCV settings, where emergency services are overstretched and formal response systems may be fragmented or absent, access to timely, credible data becomes a lifeline for communities to take action.

Access to forecasted hazard and risk data enables rapid, life-saving decisions. These include pre-positioning supplies, evacuation, activating contingency plans or triggering cash transfers, particularly where local response capacity is limited. This is especially critical where logistics are constrained, communications are fragile and complex, and the window for action is short.

But early warning is not just about technology. Bridging the gap between forecasts and action means engaging with local stakeholders, working through trusted networks or non-state actors, and tailoring systems to reflect the realities on the ground. Forecasts must be translated into information that people can understand, trust and use.

Traditional early warning systems are typically designed for stable environments. They rely on established national hydrometeorological services, physical observation networks and centralised government alerts. These systems can be highly effective where infrastructure is robust and institutions function well.

But in FCV settings, these assumptions often do not hold. Observation networks may be damaged or absent, data flows disrupted, and communication channels limited. Communities at risk may not trust, or even receive, official warnings, particularly in areas governed by non-state actors.

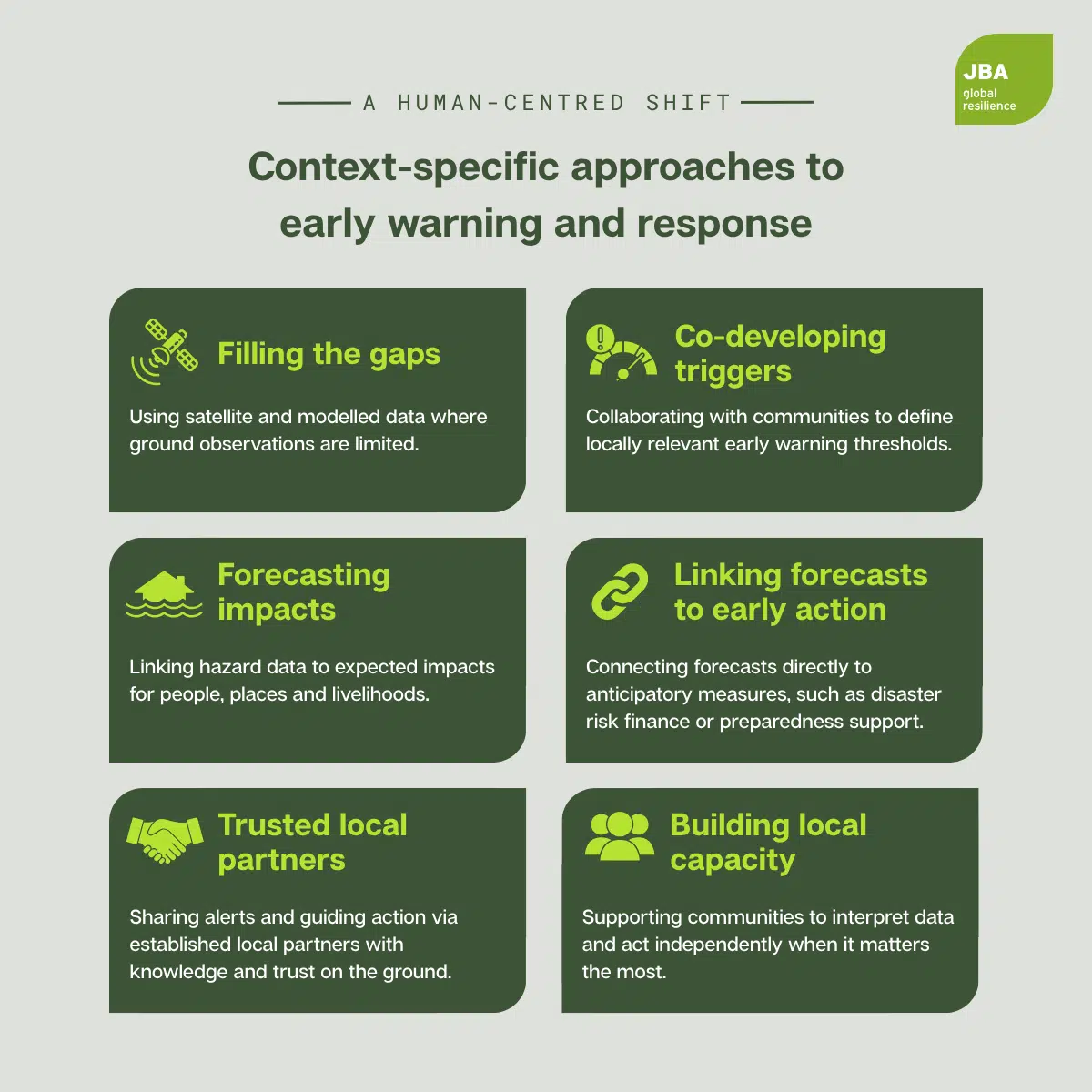

In response, newer approaches are emerging (see figure below). These reflect a shift from top-down technical systems to more decentralised, adaptive, people-centred solutions, which provide a critical lifeline in contexts where governance and infrastructure are fragile.

At JBA, we work with governments, organisations and local stakeholders to co-create early warning systems that are trusted, actionable and locally relevant. Our work includes:

These examples show how forecasting systems must be shaped by the context in which they operate. Whether in resource-constrained environments or FCV settings, where systems are fragile and trust is often low, forecasts only lead to action when they are usable, credible and locally owned.

With increasing climate shocks and escalating humanitarian needs, investment in early warning for FCV contexts is more urgent than ever. The UN’s Early Warnings for All initiative rightly calls for universal coverage by 2027. However, achieving this in fragile settings means going beyond conventional models.

It means adapting to uncertainty, valuing local voices and focusing on information that leads to action. Done well, early warning becomes part of the social fabric of resilience. Helping communities navigate uncertainty with greater confidence and dignity.

For a broader look at the global goal of expanding multi-hazard early warning systems, read What does it mean to provide multi-hazard early warnings for all?

Ready to discuss your next project? Contact our team today.

Discover more about the challenges and solutions shaping resilience and sustainable development across the globe.